Whether it is used in direct methods of attack or as an enabler for downstream cybercrime, malware remains one of the key threat areas within cybercrime. The malware identified as the current threats across the EU by EU law enforcement can be loosely divided into three categories based on their primary functionality – ransomware, Remote Access Tools (RATs) and info stealers. It is recognised that many malware variants are multifunctional however and do not sit neatly in a single category. For example, Blackshades is primarily a RAT but has the capability to encrypt files for ransom attacks; many banking Trojans have DDoS capability or download other malware onto infected systems.

Ransomware remains a top threat for EU law enforcement. Almost two-thirds of EU Member States are conducting investigations into this form of malware attack. Police ransomware accounts for a significant proportion of reported incidents, however this may be due to an increased probability of victim reporting or it simply being easier for victims to recognise and describe. Industry reporting from 2014 indicates that the ransomware phenomenon is highly concentrated geographically in Europe, North America, Brazil and Oceania1.

CryptoLocker is not only identified as the top malware threat affecting EU citizens in terms of volume of attacks and impact on the victim, but is considered to be one of the fastest growing malware threats. First appearing in September 2013, CryptoLocker is believed to have infected over 250 000 computers and obtained over EUR 24 million in ransom within its first two months2. CryptoLocker is also a notable threat amongst EU financial institutions.

In May 2014, Operation Tovar significantly disrupted the Gameover Zeus botnet, the infrastructure for which was also used to distribute the CryptoLocker malware3. At the time the botnet consisted of up to one million infected machines worldwide. The operation involved cooperation amongst multiple jurisdictions, the private sector and academia. Tools to decrypt encrypted files are now also freely available from Internet security companies4.

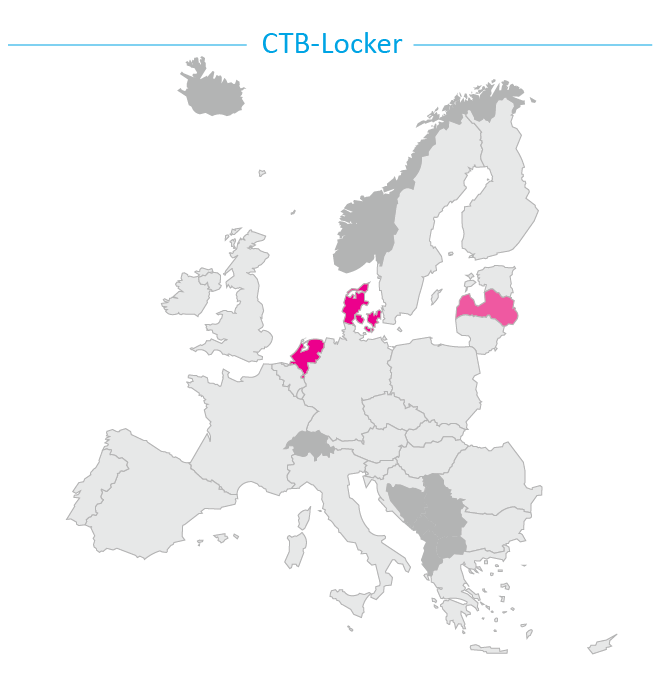

Curve-Tor-Bitcoin (CTB) Locker is a more recent iteration of cryptoware using Tor to hide its command and control (C2) infrastructure. CTB Locker offers its victims a selection of language options to be extorted in and provides the option to decrypt a "test" file for free. Although not as widespread as CryptoLocker, CTB Locker was noted as a significant and growing threat by a number of EU Member States. This is supported by industry reporting which indicates that up to 35% of CTB Locker victims reside within Europe5.

Remote Access Tools exist as legitimate tools used to access a third party system, typically for technical support or administrative reasons. These tools can give a user remote access and control over a system, the level of which is usually determined by the system owner. Variants of these tools have been adapted for malicious purposes making use of either standard or enhanced capabilities to carry out activities such as accessing microphones and webcams, installing (or uninstalling) applications (including more malware), keylogging, editing/viewing/moving files, and providing live remote desktop viewing, all without the victims knowledge or permission.

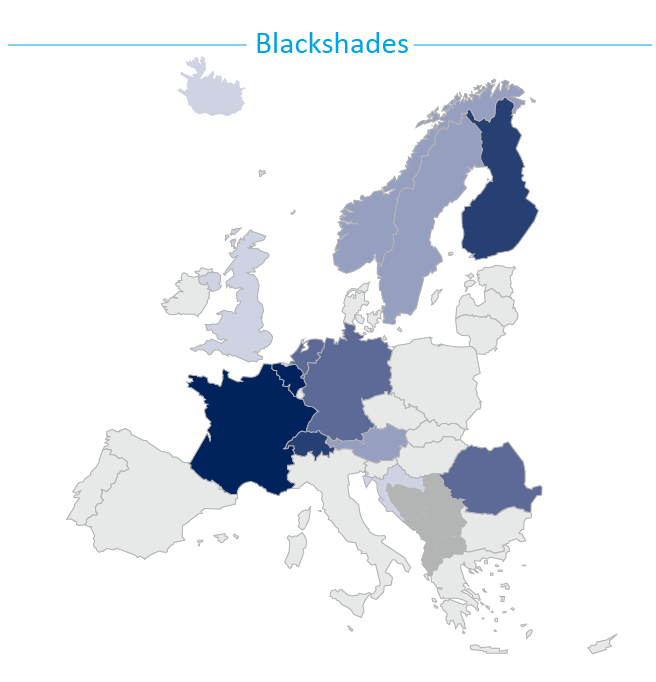

Blackshades first appeared in approximately 2010 and was cheaply available (~€35) on hacking forums. In addition to typical RAT functionality, Blackshades can encrypt and deny access to files (effectively acting as ransomware), has the capability to perform DDoS attacks, and incorporates a "marketplace" to allow users to buy and sell bots amongst other Blackshades users6.

In May 2014, a two-day operation coordinated by Eurojust and Europol's EC3 resulted in almost 100 arrests in 16 countries worldwide. The operation targeted sellers and users of the Blackshades malware including its co-author. Despite this, the malware still appears to be available, although its use is in decline.

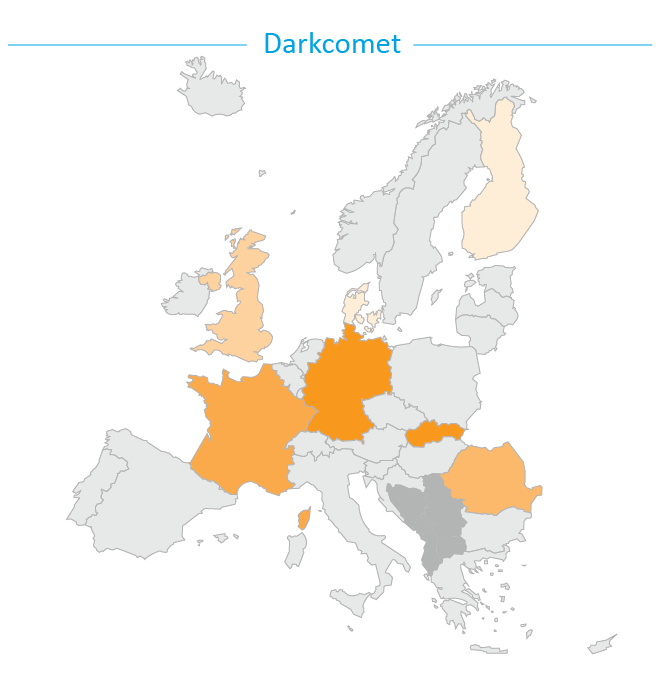

DarkComet was developed by a French security specialist known as DarkCoderSC in 2008. The tool is available for free. In 2012 DarkCoderSC withdrew support for the project and ceased development as a result of its misuse7. However it is still in circulation and widely used for criminal purposes.

Data is a key commodity in the digital underground and almost any type of data is of value to someone; whether it can be used for the furtherance of fraud or for immediate financial gain. It is unsurprising then that the majority of malware is designed with the intent of stealing data. Banking Trojans - malware designed to harvest login credentials or manipulate transactions from online banking - remain one of the top malware threats.

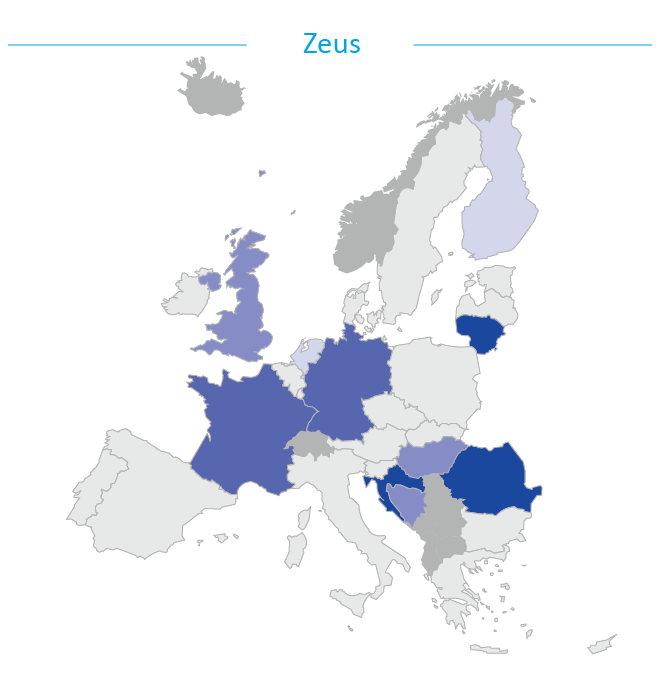

First appearing in 2006, Zeus is one of most significant pieces of malware to date. The Zeus source code was publically leaked in May 2011 after its creator abandoned it in late 2010. Since then a number of cybercrime groups have adapted the source code to produce their own variants. As such Zeus still represents a considerable threat today and will likely continue to do so as long as its original code can be updated and enhanced by others.

Gameover Zeus (GOZ) or Peer-to-Peer (P2P) Zeus was one such variant which used a decentralised network of compromised computers to host its command and control infrastructure, thereby making it more resistant to law enforcement intervention.

In June 2015, a joint investigation team (JIT) consisting of investigators and judicial authorities from six European countries, supported by Europol and Eurojust, arrested a Ukrainian cybercrime group who were developing and distributing the Zeus and Spyeye malware and cashing-out the proceeds of their crimes. The group is believed to have had tens of thousands of victims and caused over EUR 2 million in damages.

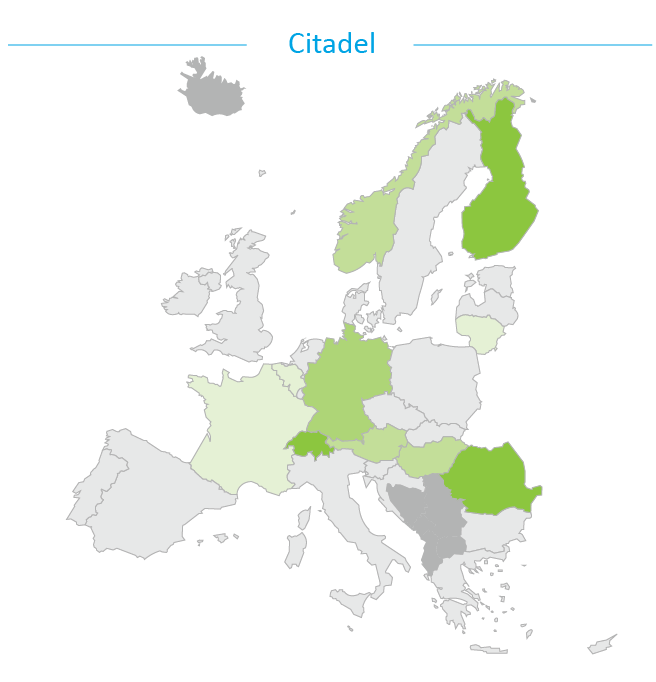

Citadel is a successful descendant of Zeus. It first appeared in circa 2012 and was initially sold openly on underground forums before being withdrawn from general distribution later that year. Its sale and use is now limited to select groups. Citadel infection rates have never reached the huge numbers Zeus itself has attained. Instead Citadel appears to be used for much more targeted (APT) attacks - campaigns targeting specific businesses or government entities8 9. Citadel has been noted as the first malware to specifically target password management solutions10.

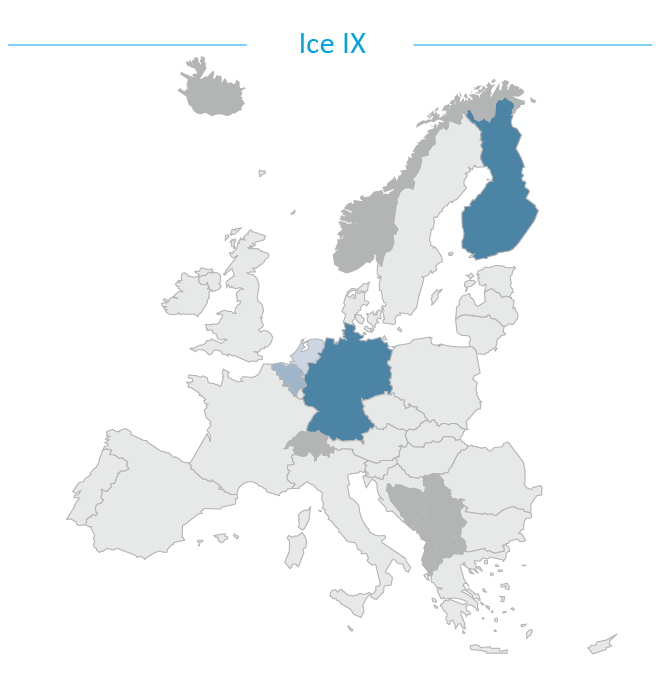

Ice IX is another first generation Zeus variant following the release the Zeus source code, appearing in the same time period as Citadel. Although its use appears to be in decline, several EU Member States have still actively investigated cases of its use.

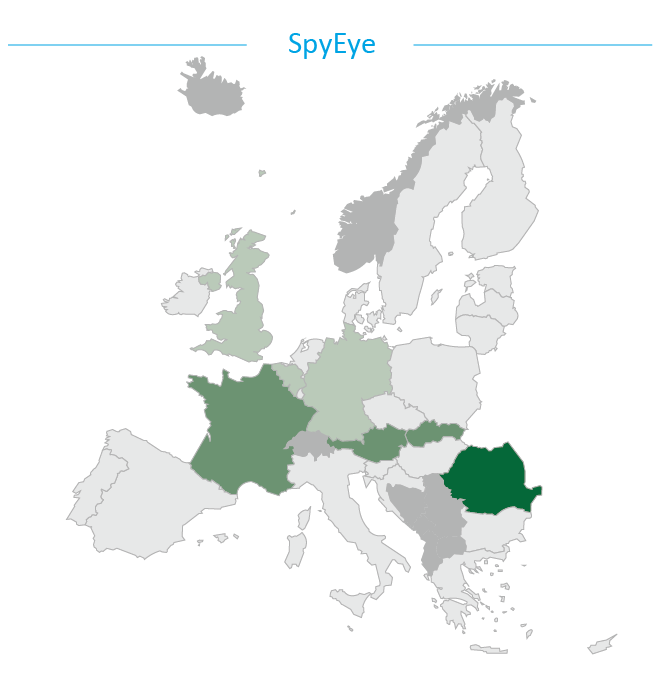

Spyeye appeared in late 2009 on Russian underground forums. Cheaper than the leading malware kit at the time (Zeus) while mirroring much of its functionality, Spyeye quickly grew in popularity. It is believed that when Zeus developer Slavik ceased Zeus's development, the source code was sold/transferred to Spyeye developer Harderman/Gribodemon, only a short while before the Zeus source code was leaked publically. In January 2014, Russian national Panin pleaded guilty before a US federal court on charges related to the creation and distribution of Spyeye. Despite this several EU Member States are still actively investigating cases related to Spyeye, although its use is apparently in decline.

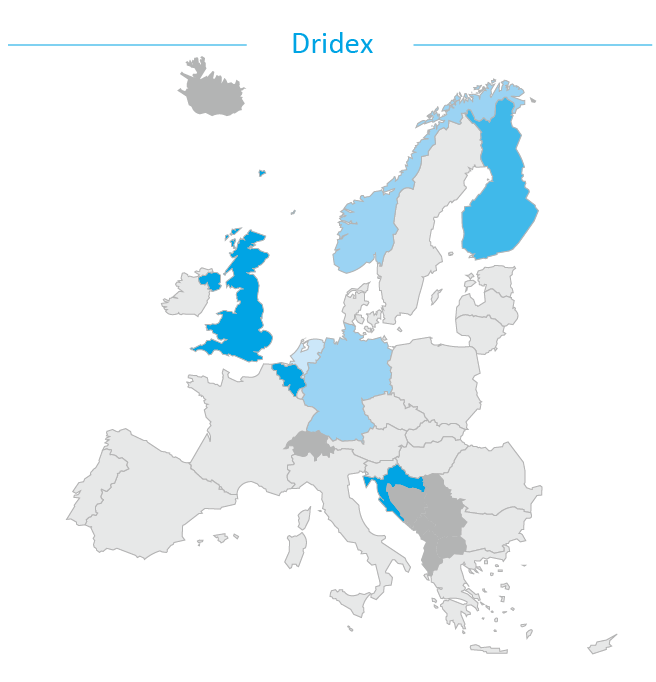

Dridex first appeared in circa November 2014 and is considered the successor to the Cridex banking malware. However, unlike Cridex, which relied on exploit kit spam for propagation, Dridex has revived the use of malicious macro code in Microsoft Word attachments distributed in spam in order to infect its victims11. Several EU Member States have encountered Dridex and, although instances are low in number, the sensitivity of the harvested data, increasing degree of sophistication and growing number of cases confirm Dridex is an upcoming threat.

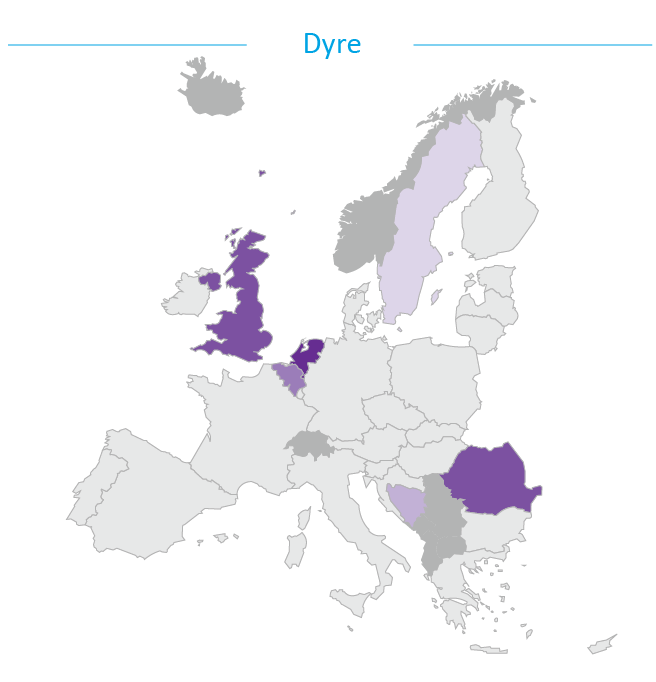

Dyre is a new malware kit which appeared in 2014, using a number of ‘Man-in-the-Browser’ attack techniques to steal banking credentials. Dyre targets over 1000 banks and other organisations including electronic payment and digital currency services, with a particular focus on those in English-speaking countries12. Some campaigns use additional social engineering techniques to dupe their victims into revealing banking details13. Dyre is also noted for its ability to evade popular sandbox environments used by researchers to analyse malware14 and by its ability to download additional malware payloads onto an infected system such as the Cryptowall ransomware15.

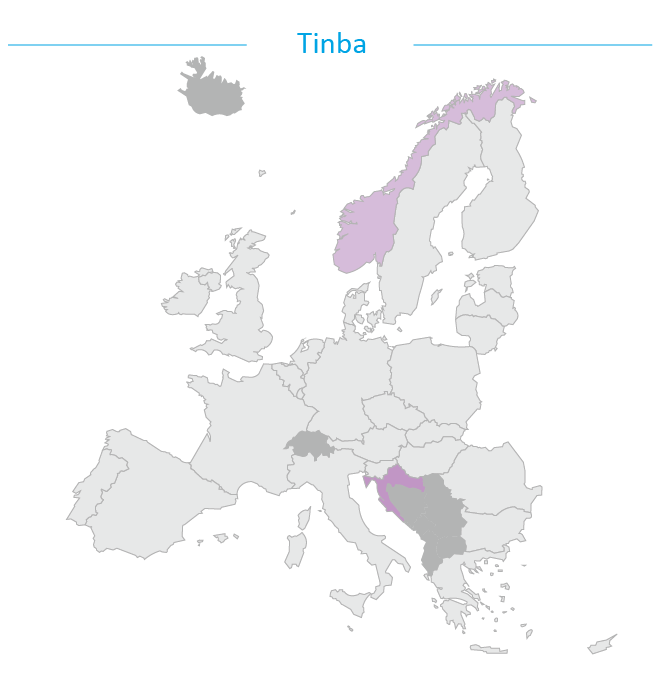

Tinba, the truncation of ‘tiny banker’ - referring to its small file size (~20kb) - first appeared in 2012. Tinba has been noted as largely targeting non-English language countries such as Croatia, Czech Republic16 and Turkey17. The source code for Tinba was leaked in 2014 allowing its ready-made code to be used by other cybercriminals for free.

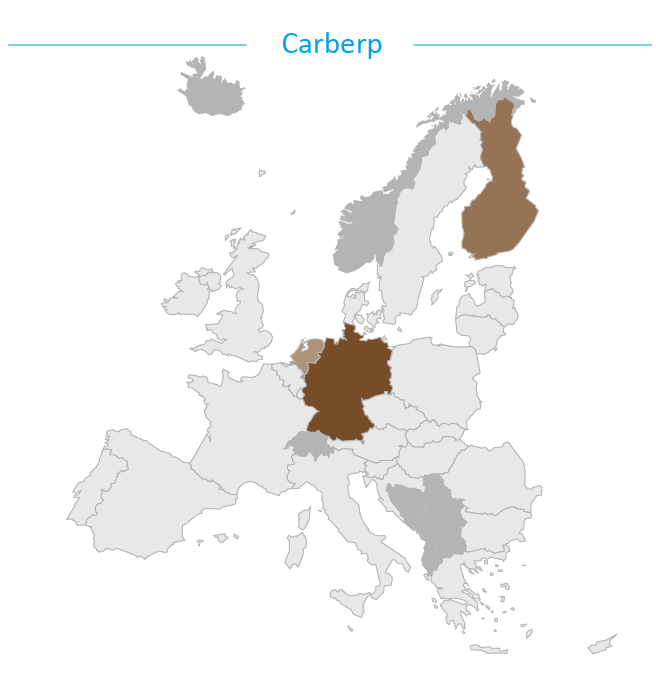

First encountered in 2010, Carberp was initially found to be only targeting Russian-speaking countries but was later modified to additionally target Western financial organisations18. The Carberp source code was leaked in June 2013.

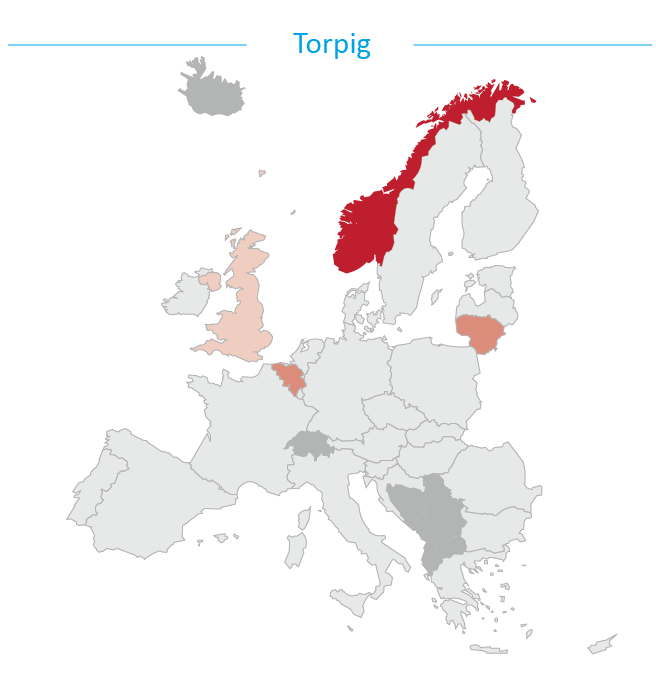

Torpig was originally developed in 2005 and was mainly active circa 2009. Torpig is installed on a system's Master Boot Record allowing it to execute before the operating system is launched making it harder for anti-virus software to detect19. Several European countries have active Torpig investigations however numbers are low and decreasing.

Shylock first appeared in 2011 and used advanced ‘Man-in-the-Browser’ attacks to steal financial data and make fraudulent transactions. Shylock is a privately owned (by its creators) financial Trojan and as such its use and distribution is highly constrained. It is not available for purchase on underground markets20. Despite successful disruption activity, several EU Member States still report significant Shylock activity.

In July 2014, a UK-led operation resulted in the seizure of command and control (C2) servers and domains associated with the operation of a Shylock botnet consisting of 30 000 infected computers. The malware campaign had largely targeted customers of UK banks. The operation involved cooperation between several other jurisdictions, private sector companies and CERT-EU, and was coordinated by EC3 at Europol.

Although the harm deriving from any malware attack is ultimately the result of one of the above mentioned attack methods, there are many other types of malware which facilitate or enable these attacks. These malware products are infrequently the main focus of law enforcement activity as it is the malware they enable that will spark an investigation. These enabling malware products are offered 'as-a-service' on the digital underground.

Exploit kits are programs or scripts which exploit vulnerabilities in programs or applications to download malware onto vulnerable machines. Since the demise of the ubiquitous Blackhole exploit kit in late 2013, a number of other exploit kits have emerged to fill the vacuum. Some of the current, most widely-used exploit kits include Sweet Orange, Angler, Nuclear and Magnitude21.

One of the most common methods of malware distribution is by malicious email attachment and the most productive way to reach the most potential victims is via spam. The primary function of some malware is to create botnets geared to generate large volumes of spam. One such example of such ‘spamware’ is Cutwail which has been known to distribute malware such as CTB Locker, Zeus and Upatre22.

The core function of some malware is simply, once installed, to download other malware onto the infected system. Malware such as Upatre is one such product and has been observed downloading malware such as Zeus, Crilock, Rovnix and more recently Dyre23. Upatre itself is commonly distributed via malicious email attachment distributed by botnets such as Cutwail.

In April 2015, Europol’s EC3 and the Joint Cybercrime Action Taskforce (J-CAT), joined forces with private industry and the FBI to support Operation Source. This Dutch-led operation targeted the Beebone (also known as AAEH) botnet, a polymorphic downloader bot that installs various forms of malware on victims’ computers. The botnet was 'sinkholed' and the data was distributed to the ISPs and CERTs around the world, in order to inform the victims.

Industry reporting indicates that the volume of mobile malware continues to grow, although some reporting suggests that the rate of growth is decelerating24 or that infection levels are even decreasing25. While it remains a recurring, prominent and contemporary topic in both industry reporting and the media, mobile malware currently does not feature as a noteworthy threat for EU law enforcement.

The majority of mobile malware is typically less malicious than its desktop counterpart. Although there is a growing volume of banking malware and trojanised financial apps on mobile devices, the majority of mobile malware is still from premium service abusers, i.e. those that subscribe victims or make calls to premium rate services. It is less probable therefore that a victim would feel the need to report an attack due to the relatively small losses incurred. Furthermore, victims are more likely to either reset their own device or take it to a phone repair shop, than they would be to take it to a police station. Reporting of this threat is therefore low and consequently the law enforcement response is minimal.

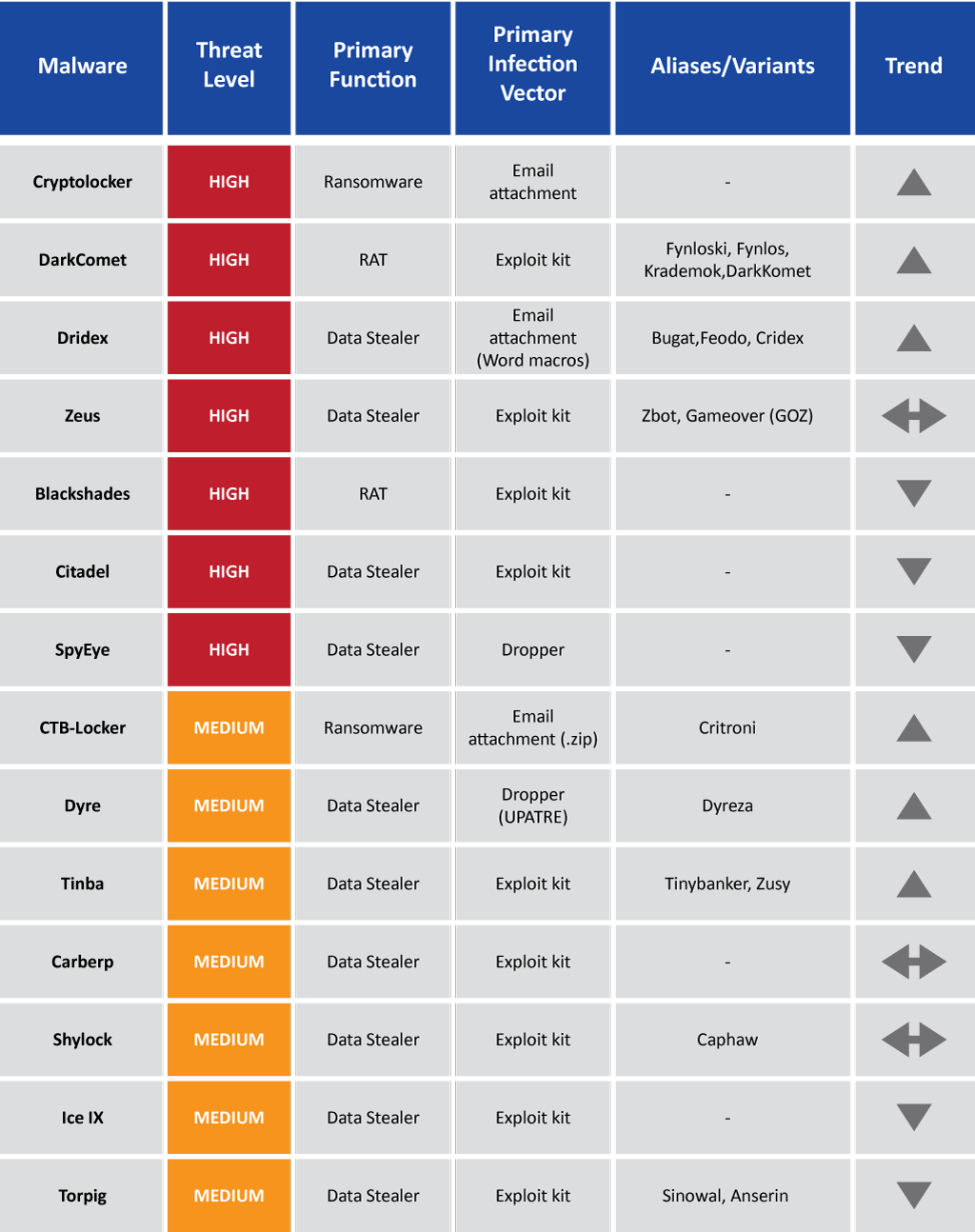

The following table highlights the threats posed by different malware variants reported to and/or investigated by EU law enforcement.

The recent experiences and investigative focus of European law enforcement suggests that the top malware threats of the last 5+ years are steadily in decline as a new generation of malware comes to the fore. Although some variants remain a threat, the investigation rates of Zeus (plus its variants Ice IX and Citadel), Torpig, Spyeye and Carberp have either plateaued or are in decline. Many of these products have had their development and support discontinued by the developer either voluntarily or as a result of their arrest. The continued threat posed by these products is likely due to their availability, with the source code for most publically leaked. Instead, newer names on the malware scene such as Dridex and Dyre are becoming more prominent in law enforcement investigations, a trend which is likely to increase.

A common and perhaps inevitable fate for any malware is to have its source code publically leaked, either by a rival criminal gang or by security researchers. Whilst this may be of tremendous benefit to the Internet security community it also puts the code into the hands of prospective coders allowing them to rework and enhance the code to create their own products with a large part of their work already done for them. As an example, a hybrid of the Zeus and Carberp Trojans, dubbed Zberp, was detected in mid-201426. It is likely that, given the success and sophistication of many of the older malware products, we will continue to see new threats which draw on their code.

Similarly newly published vulnerabilities are rapidly incorporated into exploit kits. This often occurs faster than patches can be released and almost certainly quicker than most potential victims would update their software. As an example, the Zero-Day exploits which were released as a result of the Hacking Team exposure in June 2015 appeared in the Angler, Neutrino and Nuclear exploit kits within days27.

As more consumers move to mobile devices for their financial services (banking, mobile payments, etc) the effectiveness and impact of mobile malware will increase. It can therefore be expected to begin to feature more prominently on law enforcement's radar.

One advanced technique that we can expect to see further future examples of is the use of 'information hiding' methods such as steganography. Rather than simply encrypting data so that it is unreadable, such techniques hide data within modified, shared hardware/software resources, inject it into network traffic, or embed it within the structure of modified file structures or media content. Malware employing these techniques can, for example, stealthily communicate with C2 servers or exfiltrate data. It may therefore become increasingly difficult to detect malware traffic if such methods become more widely employed. Smartphones may be particularly vulnerable to such malware as, coupled with their array of in-built sensors, they provide additional channels via which hidden data can be transmitted28.

Click here to open this table

Click here to open this table